A wake-up call

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia galvanised the developed countries, through the auspices of the IEA, into concerted action to safeguard oil supplies; this response was prompted by recognition of Russia’s role in the petroleum industry as the world’s second-largest crude oil producer and largest exporter of refined oil products.

Closer to home, Russia supplies about 30% of Europe’s oil requirements; for the UK it accounted for around 10% of total crude oil imports and around 18% of diesel requirements.

In March of this year, IEA countries agreed to release 62.7 million barrels from emergency oil stocks, to be available over 6 months and, on 1st April, a further 120 million barrels – the largest stock draw in the organisation’s history, with the UK’s contribution being 4.4 million barrels.

At the same time, on 31st March, the USA announced a 180 million barrel drawdown over 6 months from its Strategic Petroleum Reserve , of which about 60 million barrels will be its contribution to the wider IEA initiative.

These actions seek to both bring a measure of stability to oil markets and serve notice of intent to prepare for the consequences of possible disruptions to Russian supplies.

From this macro perspective we will now take a closer look at the UK and how it is fixed in terms of vulnerabilities to supply continuity and security and measures to try to safeguard and protect these.

Supply/demand balances & compulsory holdings

We will start by looking at two key features of the architecture around supply security;

firstly- products’ balances, which will show the measure of dependency on non-indigenous sourcing.

As with the other large European oil markets, France and Germany, the UK is, and has been for a long time, in structural deficit on the main middle distillates grades and in surplus on motor spirit.

By and large, this is a consequence of refinery investment decisions in the 1970s and 1980s, which focused on upgrading facilities (such as FCCs) to produce more petrol rather than diesel or Jet A1, both of which have experienced significant demand growth in the current millennium.

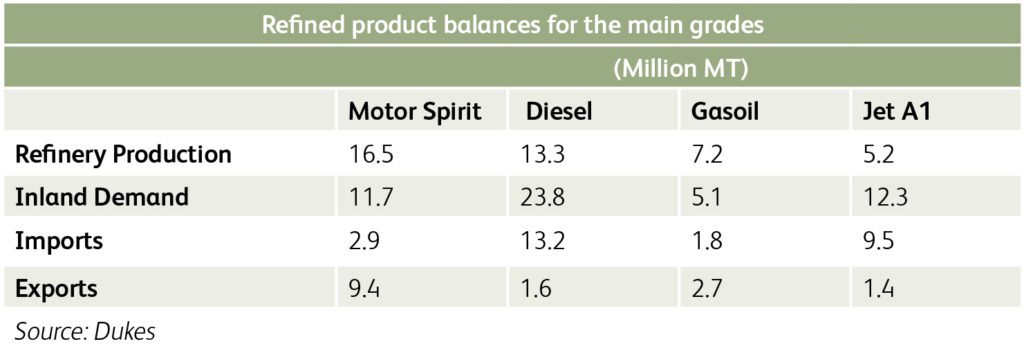

The table below illustrates the point, taking the last pre-covid year, 2019.

This shows that import dependency for diesel represents around 55% of inland demand and, for Jet A1, just over 75%. About 35% of diesel imports were sourced from Russia, while Saudi Arabia and then Kuwait, were the main sources of Jet A1 imports.

The deficit position on both grades has been growing steadily during the current millennium, with the pattern not changing significantly in the past two (post- covid) years.

Crude oil supply and demand is more or less in balance with exports and imports being of similar magnitude. The main sources of imports are Norway and the USA.

Secondly – compulsory stocking. Under current compulsory oil stocking arrangements in the UK, refiners & ex- refiners are obliged to hold 67.5 days of inland consumption and with importers and wholesalers obliged to hold 58 days.

Additional provisions, introduced in 2012, require that, for motor spirit, diesel/gasoil and jet kerosene, at least 22.5 days of the total obligation must be carried as finished products.

For the balance of the obligation for these grades (45 days for refiners and 35.5 days for importers) and, for the full obligation (67.5 days & 58 days respectively) for fuel oil and regular kerosene, this can be met by a category termed ‘Any Oil’ (which, effectively, encompasses the full refined products slate, as well as crude oil, feed stocks and NGLs) .

Assessment of risks and mitigation measures

In 2013, consulting firm, Purvin & Gertz, was commissioned by the Government to conduct a review into the supply capability of indigenous UK refineries in the face of concerns around rising import dependency for middle distillates grades as well as more specific regional supply issues.

The review concluded that in the 4 geographic supply envelopes assessed:

- The South was in deficit on all product grades, so regarded as neither robust nor resilient

- The Central area was in surplus on all grades except diesel – but readily accessible, via pipelines, to existing refineries, so deemed to be both robust and resilient

- Scotland was similar to the Central area in being viewed as robust, but not resilient due to insufficient terminal capacity to compensate for loss of Grangemouth refinery supply

- Northern Ireland was (and is) entirely import dependent.

A review by DECC (now BEIS) followed in 2014, which concluded that resilience and security of supply were best supported by ‘retaining a mix of domestic refining and imported product’ and that this ‘is consistent with the government’s energy security of supply strategy which recognises the benefits of supply diversity’.

Among other things, it recommended the establishment of a Midstream Oil Task Force as a joint government/industry group to ‘look at how best to support refinery and midstream businesses in the wake of a reduction in the size of the refining sector and provide a strategic and collaborative way for government and industry to work together and to deliver the actions from the review’.

This body complements the work of the established Downstream Oil Industry Forum (DOIF), set up at the start of the current millennium.

The Downstream Oil Resilience Bill

In 2017, BEIS instigated a consultation among interested parties on measures that should be introduced to enhance oil supply resilience by seeking greater regulatory oversight of the ownership and operation of key fuel supply assets. Following a gap of 4 years, this process resulted in the presentation to Parliament, in June 2021, of The Downstream Oil Resilience Draft Bill.

The purpose of the draft Bill is to (1) to address threats to security of fuel supply by providing the Government with the measures to build resilience in the downstream oil sector, and (2) to help protect fuel supply resilience when required and prevent supply disruptions from occurring in the first place.

The key measures to achieve these ‘outcomes’ will be as follows:

- Enabling the Government to direct companies to take necessary action to ensure resilience and security of fuel supply, if necessary.

- Ensuring that new owners of critical fuel infrastructure are both financially sound and operationally capable.

- Enabling the Government to provide financial assistance to build resilience and ensure security of supply if necessary.

- Creating a number of new civil and criminal penalties under which a company and its officers may be liable for failing to comply with a direction, making false statements and failing to provide required information.

- Allowing the Government to collect information from the sector to understand the impact of potential or active disruptive events

The resulting consultation (now closed) viewed the UK petroleum products market as a mature one, facing both changing patterns of demand and high levels of global competition which, in turn, has apparently created:

- fragmenting supply chains; with major oil companies, which used to run vertically- integrated well-to-pump operations, divesting themselves of categories of assets or outsourcing some operations.

- relatively high utilisation rates and closures of spare or uneconomic capacity. For example, there are, currently, six UK oil refineries (down from a high of 19 in 1975) and the number of filling stations has declined from around 18,000 sites in 1990 to 8,400 now.

Managed efficiently, flexibly and effectively

The consultation also found that, despite these developments, the sector seems to be managed efficiently, flexibly and effectively in ensuring continuity of fuel supply but accidents, severe weather, malicious threats, industrial action and financial failure present significant supply chain disruption risks. The effects of Brexit and Covid-19 represent additional uncertainties.

The proposed legislation marks a significant departure from the government’s existing powers to monitor and control fuel supplies, which are limited, as per the 1976 Energy Act , to instances where there is an ‘actual or threatened emergency’ to supplies, and limited powers to intervene in mergers, on grounds of national security, under the Enterprise Act 2002.

However, it states that the new powers would be used only as a ‘back-stop’ to protect fuel supply resilience ‘when required’. No new requirements are sought to control operator crude or fuel inventory levels. The timetable for passage of the proposed legislation is not yet clear; suffice it to say that once approval has been granted, including any changes which may be made, the Bill will come into force on a date the Secretary of State will set by regulation.

Measures to safeguard the security and continuity of oil supply were already ‘in train’ from the middle of last year and the need for such provisions has been greatly sharpened by the unfolding events in Ukraine. They equally have an important role to play in ensuring an orderly transition away from dependency on oil by the implicit acceptance that it will continue to be a key source of energy, especially for the transport sector, for several years.

Rod Prowse worked for 30 years across the full spectrum of the downstream oil sector, in both the UK and USA, which has included leadership positions in both retail and wholesale fuels businesses. Rod draws on his extensive knowledge of this global industry to bring us ‘Industry Insights’.